Like a lot of you I grew up watching TV and movies, everything from Little House on the Prairie to Back to the Future. Those mediums have changed society’s perception of story. Screenwriters divide their scripts into scenes. My abundance of screen-time programmed my brain so when I pick up a novel I prefer ones that read like movies, stories divided into scenes.

Lisa Cron, author of Wired for Story, gave this definition of story, “A story is about how the things that happen affect someone in pursuit of a difficult goal, and how that person changes internally as a result.”

Lisa Cron, author of Wired for Story, gave this definition of story, “A story is about how the things that happen affect someone in pursuit of a difficult goal, and how that person changes internally as a result.”

So what’s a scene? A scene is a piece of a story. It consists of ONE main conflict which causes a change in the main character.

Legendary director Mike Nichols said, “There are only three kinds of scenes: a fight, a seduction or a negotiation.” Before I compose a scene I first decide which of these categories it falls into.

Fight – moving forward with difficulty (pushing through a crowd or overcoming physical obstacles) or a campaign for or against something, to put right what one considers unjust.

Seduction – deliberately enticing a person, to engage in a relationship, to lead astray, as from morality; to corrupt, to persuade

Negotiation – intended to reach a beneficial outcome for all parties involved, or for just one

Once I know if I’m writing a fight, a seduction or a negotiation I determine the main conflict. Only one main conflict. Many beginning writers try to stuff too much, and too many characters, into a scene. One time when a student at the Santa Barbara Writers Conference read a piece the workshop leader, renowned editor Shelly Lowenkopf, pulled over a pitcher of water. At the end of the reading Shelly tipped the pitcher to his glass, said, “What you have here is…” He let the water run over the top of the glass onto the tablecloth. The lesson, don’t make a mess of your scene.

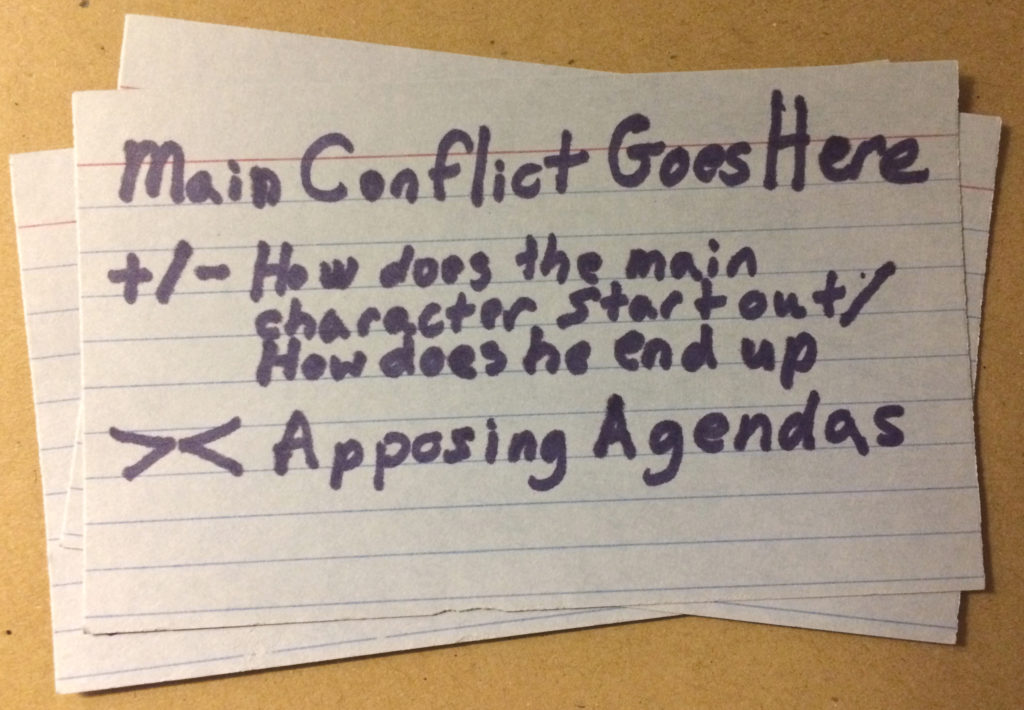

The rest of the method I use for writing scenes comes from the late great Blake Snyder in his book Save the Cat. Snyder discusses how to map out a screenplay but like I said a good twenty-first century novel mimics a movie. I dig out an index card, write the main conflict at the top.

Then I make the +/- symbol next to where I note the emotional change the main character goes through in the scene. Snyder said, “I can’t tell you how helpful this is in weeding out weak scenes or nailing down the real need for something definite to happen in each one.” He then stresses the importance of how the character in pursuit of the goal reacts to what happens in the scene.

Next comes the >< symbol which represents the opposing agendas in the scene. What does each person or entity want? If the characters don’t conflict, it’s not a fight, a seduction or a negotiation, thus no scene. Plus, if I try to write dialog without conflict, it’ll sound like conversation, which is not dialog.

In its perfect form a scene becomes a mini story. Each scene must contain a character with a goal, something that gets in his way, and the character’s reaction to that obstacle.

If I fail to find an index card among the clutter I call my office, I’ll type the plan for the scene at the top of the empty page. That way I don’t have the anguish of staring at a blank screen and I can delete notes once I have the scene fleshed out. In a simple few lines I state:

- the main conflict

- what each character wants in the scene

- how what happens in the scene changes the main character.

When you read novels and memoirs or watch movie and TV, keep your eye out for scenes. The more you recognize scenes in other work, the easier you find writing them yourself. Take a look at some examples of scenes from books you may’ve read:

The Girl on the Train by Paula Hawkins

Rachel calls Tom to find out how she got cut.

+/- Rachel starts out frustrated, ends up way more frustrated

>< Rachel wants to know what Anna did; Tom wants to know Rachel’s connection to the Hipwells.

I Was Here by Gayle Forman

Cody visit Ben to find out more about him.

+/- Cody starts out suspicious, ends up confused

>< Cody wants to measure Ben’s boundaries at acting a Casanova; Ben wants Cody to know he’s not what she thinks.

Room by Emma Donoghue

Ma confesses to Jack that the real world depicted on TV exists beyond where they’re confined.

+/- Jack starts out ambivalent, ends up open to the idea

>< Jack wants his world to stay the same; Ma wants Jack to understand the truth.

Back Roads by Tawni O’Dell

Harley’s youngest sister, Jody, engages him in a discussion about parental behavior.

+/- Harley starts out lighthearted, ends up feeling the responsibility of his surrogate parenthood

>< Harley wants to do anything else but answer Jody’s questions; Jody wants to know if people still love each other even if they fight.

The Help by Kathryn Stockett

Skeeter tells Constantine a boy called her ugly.

+/- Skeeter starts out feeling hopeless, realizes she has a choice in what she believes

>< Skeeter wants to feel sorry for herself; Constantine wants her to see that she’s beautiful on the inside.

Pingback: How many types of scenes are there? – Carrie Jones Books

Lisa,

This is a great little exercise to clean up scene construction and getting clear on goals.

I just ran a scene that I wrote today through it and realized it’s motivations are pretty murky.

Thank you.

Charley